“Who d’ya think you’re talking to?”

It could easily be a provocative jab from a tipsy punter down your local, but actually it’s the first thing you should ask yourself before communicating.

Yes, audience is key and once you know who you’re trying to reach, everything else should fall into place. Think about who you’re talking, writing or presenting to. What are their expectations, knowledge, concerns? What kind of language should you use? Will a key message be lost because it’s wrapped up in jargon or will the technical term reassure?

In media training we look at some key components to good communication and their value stands whether you’re in front of a microphone, lectern, staff meeting or computer. I find once I remind an expert to think about who they’re talking to, they become clearer and more compelling. Of course if you’re not in a media situation but actually talking to fellow experts, throw in the jargon and complexity – but don’t be afraid to liven it up with examples. More on examples later.

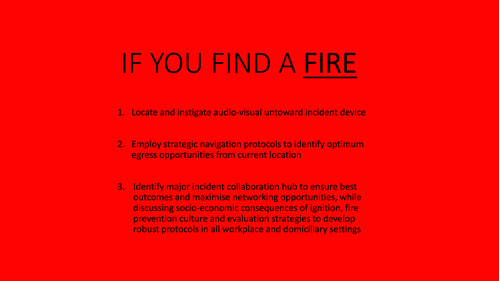

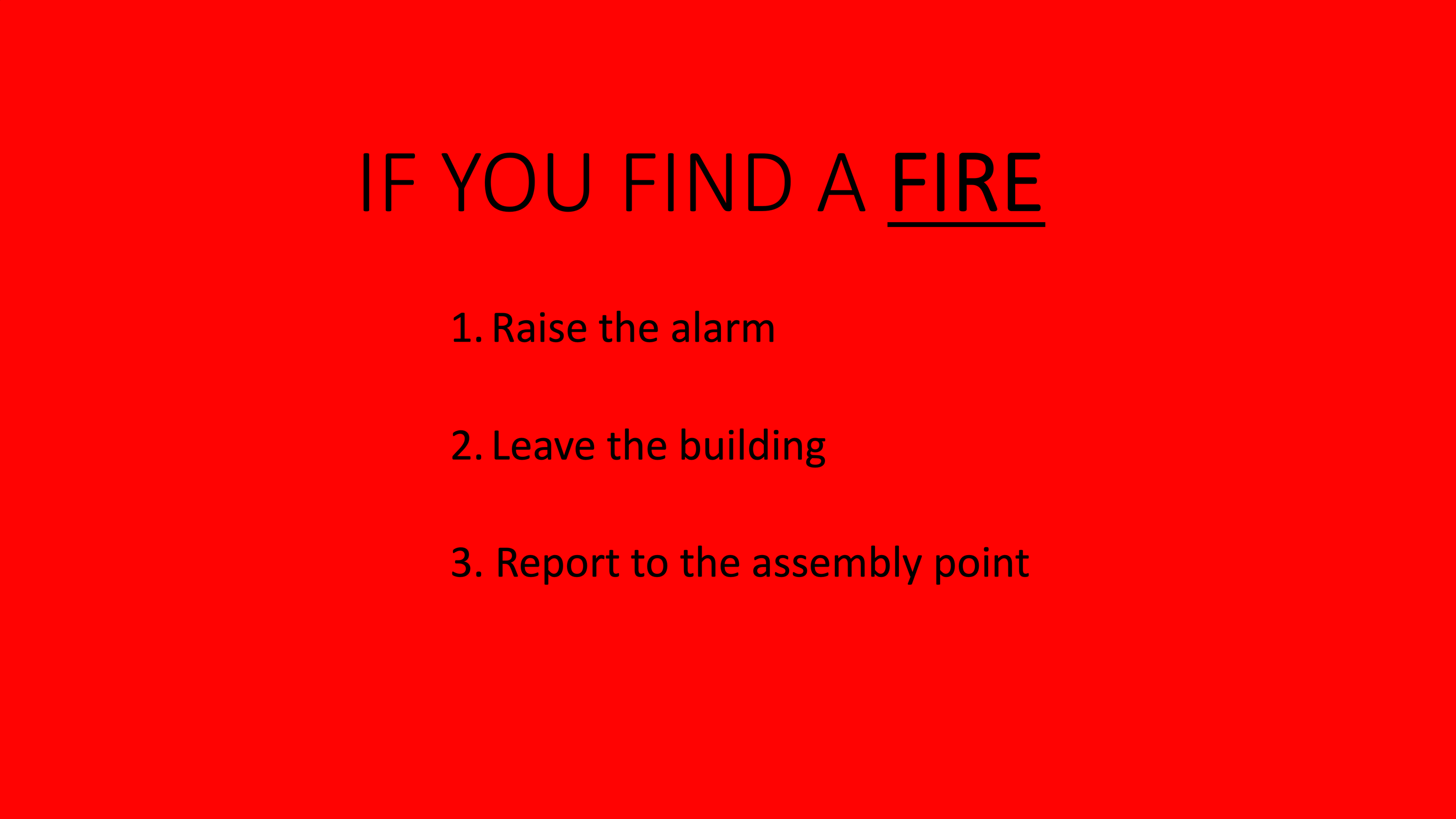

Jargon: it has its place amongst experts because it allows you to be specific and saves time. But use it with the right audience. This is my favourite tongue-in-cheek way of making the point:

Once you know your audience, you know your message. I tell media training delegates: “if you’re not sure what your message is, ask yourself why you’re doing the interview.”

When deciding messages, think about what response or change you’re looking for. That should give you your message. Accuracy and consistency with your organisation’s position is of course taken as a given.

Examples and evidence are the lifeblood of a media interview. They help us see and believe what you’re saying. The same goes for general communication. Of course, the complexity and detail will vary according to the audience and context, but examples are a great way of being more engaging and persuasive. If you were taking action to reduce infection in a hospital, you’d say what you were doing and perhaps share results if reliable.

Sorry to break it to you, but not everyone likes what you say or do all the time. Sometimes your audience will have a negative or challenging attitude and some tough questions. As part of your preparation, find out any concerns and try to abate them. Some may be rooted in misunderstanding which you can put to rest. Some might be well-founded and need to be acknowledged and addressed.

The point is, anticipate and deal with your audience’s concerns. Think about which challenges to proactively raise and confront in your communication. Focus on those obvious ones which are likely to be on people’s minds. But be ready to react to others that come up.

The above titles make up a convenient acronym: AMEN. It’s a handy way to remember them.

Media trainers often talk about the ABC of handling tricky or irrelevant questions. It’s a technique about honestly dealing with a question but not letting it sidetrack you from getting across your key messages. It’s not about sweeping things under the carpet. It’s about remembering you’re communicating for a reason.

Let’s look at ABC in a journalistic setting, for example, a typical question from a report in a norovirus outbreak:

“Hospital patients and families will be distraught that you’re limiting visiting hours”

Address the question: “We know this will be upsetting for patients and families, as a nurse I know visiting is so important for our patients and their loved ones”

Bridge away: “However we have to put our patients’ safety first”

Communicate a key message: “By reducing visiting hours for a short time we can help stop this virus being brought into our hospital and keep our patients safe. We’ll still do everything we can to allow some visiting in a reduced, safe way.”

ABC is a technique that can be used in other communication, but the right balance must be struck. Sometimes, when dealing with an agitated audience at an event, the job might be more to listen than to lead the agenda. In whatever setting it’s used, ABC should be an aid to authenticity and honesty.

You may have heard of the three Rs of crisis communication:

Regret (empathy, acknowledging human impact)

Reason (explaining cause or outlining investigation)

Remedy (explaining action or committing to take any needed)

The key is to be human while explaining what you’re doing about the situation.

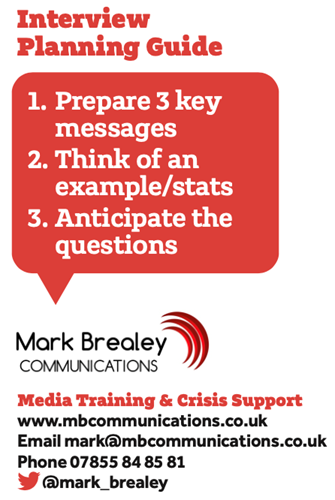

Finally, we’ve looked here at how media skills can be used in wider communication. Your communications team should lead on all media work in your organisation. If you do find yourself dealing with a journalist, make sure it’s been arranged and prepared in collaboration with your comms team. The back of my business card has a handy guide to help you prepare for interviews:

Webinar recorded for HIS: https://his.org.uk/resources-guidelines/media-training-webinar/

10-min media skills guide: https://www.mbcommunications.co.uk/10-min-media-skills-masterclass/

@mark_brealey